Part 1 - The New Brand Builders : The Market Power of Icons, Influencers, and Creators

Iconic actors, musicians, and athletes. Digital influencers. Creators. Why do companies pursue relationships with these individuals for brand-building purposes? How can old ways of thinking and long-established practices limit the engagement and effectiveness of those relationships? Why do audiences and fans believe in and care about these individuals, and when do their actions merely contribute to the noise of digital life, evoking disbelieving eye rolls rather than enthusiasm for a brand’s products and services?

Icons

Brands and marketers have a more than century-long relationship with iconic artists and athletes – starting with the first endorsement deal with London actress Lilli Langtry and Pears Soap in 1882. Other noted deals that followed include Babe Ruth in the 1920s and 1930s for items ranging from underwear to candy bars, Chuck Taylor with Converse for a branded shoe in 1932, two thirds of the top box office Hollywood stars with cigarette endorsements in the 1930-40s, countless athletes for beer commercials in the 1970s, Michael Jackson with Pepsi in the 1980s, and a multi-decade relationship that bridged two centuries for both William Shatner with Priceline, and Michael Jordan with Hanes and Nike.

Influencers

The reality of modern-day digital influencers is about two decades old – if you count the early monetized influence of the turn of the century “mommy-blogger” community as the starting point. What began as the creation of digital community and personal storytelling evolved into expansive financial relationship with brands and advertisers interested in accessing the highly engaged audiences of both niche (nano and micro) and mega celebrity digital influencers such as MrBeast and Liza Koshy on YouTube, and Charli D’Amelio and Addison Rae on Tik Tok.

Creators

Today’s creators are a diverse group – including YouTubers, podcasters, gamers, world-builders, designers, and newsletter writers – who are just starting to flex their potential brand power in ways that may embrace or reject relationships with companies as they focus on the development of their own craft, community, and personal brand.

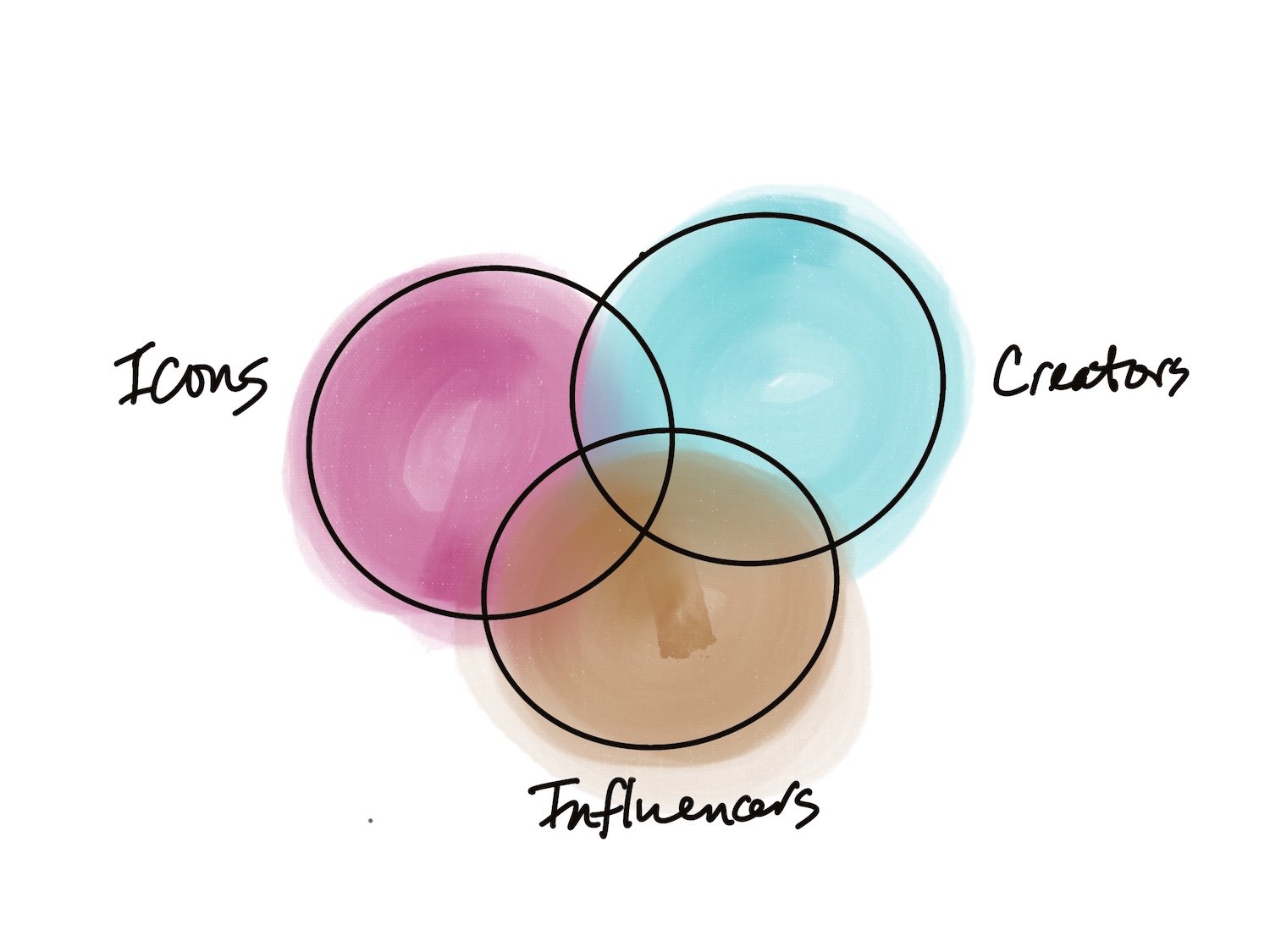

These three groups – icons, influencers, and creators – are part of a dynamic Venn diagram of potential market power, with constant growth within, and bleed-over between, the once well-contained categories. In today’s hyper-connected and performative world of social and digital platforms, individuals can begin their life in one world and then may extend into, but not be limited by, another. This bleed-over can look like:

(1) An iconic actor-musician-athlete can also become a digital influencer in practice and not just in follower numbers. This is the case of Doja Cat and her ‘marketing unicorn’ relationship with Taco Bell. Her brand power is not limited to social channels as it may be for the digitally native influencer.

(2) As a result of the extent of their reach and fan engagement, a digital influencer may become a celebrity and engage in celebrity-like activities (movie premieres and luxury brand collaborations), but they do not become an iconic artist or athlete. They may choose to develop their own products and/or build relationships with companies. Emma Chamberlain is a classic example.

(3) A member of the diverse ‘creator community’ can become a digital influencer. This is the case for Grace Wells and the video series she created, “Making Epic Commercials for Random Objects”, that launched an unexpected career. Creators may (or may not) remain perfectly happy as a master of their niche without any regard to a relationship with outside brands, or they may be hired by brands to create if they have unique media production (video, photography, and audio) skills. Grace Wells moved into digital commercial direction for brands including Sabra, Gain, Miracle Gro, and Adobe.

With these dynamic changes and the blurring boundaries between groups - artists, athletes, influencers, and creators are now re-evaluating their audiences and the kind of brand relationships that make sense to them. And bonus news for the other side of the brand equation. For entrepreneurial startup companies that choose to use the leverage of their equity – they can close deals with these individuals that once only considered Fortune 500 brands with seven-figure plus cash budgets.

If brands still hope to garner some of the new halo effect of engagement of these individuals, they must jettison some of their past principles and best practices that have limited them to ‘face of’ endorsement deals. More strategically expansive, practically effective, and values-driven relationships with an iconic individual or influencer of choice need to be undertaken now.

For insights into the nature of these changing relationships and what increases the possibility of success for decisions that are as much a result of art as of science, I tapped into the experience and perspectives of people who are leaders in reforging brand engagement.

Adam Lilling, the Founder and Managing Partner of PLUS Capital, is the trusted advisor to 70+ artists, athletes and cultural leaders - facilitating a new kind of investor-partner relationship with venture-backed companies.

Brendan Gahan, a partner and Chief Social Officer at the creative agency Mekanism looks at the world of social media and digital influence through lenses of deep personal experience, metrics and psychology.

Sarah Penna is an original in the world of creator community talent development and company building, starting as an early YouTube talent manager and now as a business leader at Patreon, where she launches high-profile creator partnerships.

In This Series on The New Brand Builders:

Part 2 - Paid Mercenary or Energized Investor? Artists, Athletes, and Their New Relationship with Brands.

Part 3 - Digital Influencers and Creators Take Control of Their Economic Destiny. Brands Should Take Notice.